Early Life and Roots

I often find myself drawn to the stories of those who shaped early America, like Augustine Warner Jr., a figure whose life bridged the old world and the new. Born on June 3, 1642, in the fledgling Colony of Virginia, likely in York County, he entered a world of untamed wilderness and budding ambition. His father, Augustine Warner Sr., had crossed the Atlantic from Norfolk, England, around 1628, establishing himself as a planter and councilor. His mother, Mary Towneley, hailed from Lancashire gentry, infusing the family with a touch of English refinement amid the tobacco fields.

As a young boy, Warner Jr. absorbed the rhythms of plantation life. At age 16, in 1658, he sailed back to England for education at the Merchant Tailors’ School in London. Imagine him, a colonial lad amid the bustling streets, soaking in knowledge that would later fortify his role in Virginia’s elite. He returned in the early 1660s, ready to claim his place. Short sentences capture the essence: He adapted. He thrived. By his mid-20s, he had married Mildred Reade, around 1665 to 1671, linking his fate to another prominent family.

Family Ties: The Warner Web

To me, family is like a huge oak tree, with its branches influencing successive generations. American history was shaded by the canopy of Augustine Warner Jr.’s family. His parents laid the groundwork: Mary Towneley (1614-1662), whose ancestry hinted to old English halls, and Augustine Sr. (1610-1674), a shrewd immigrant who accumulated land and sat on the Governor’s Council.

Layers were added by siblings. Robert E. Lee was the offspring of Sarah Warner’s marriage to Lawrence Towneley. Records are like morning mist, but Isabella Warner may have been another. A strategic relationship was formed when Warner Jr. married Mildred Reade (1643-1686), the daughter of Colonel George Reade and Elizabeth Martiau. Resilience was introduced by Mildred, who had French Huguenot ancestry through her grandfather Nicolas Martiau. She remarried Lawrence Washington and then Henry Gale after Warner’s passing, adding even more strands to her web.

Despite disaster pruning the branches, they had six children. Augustine Warner III (1666–1687) died young and single. Mary Warner (c. 1664–1700) married John Smith of Purton, and her descendants went on to become Queen Elizabeth II. George Washington’s paternal grandmother was Mildred Warner (1670–1701), who wed Lawrence Washington. Fielding Lewis’s grandparents, Elizabeth Warner (1672-1720) and John Lewis, were married. Both Robert Warner and George Warner (c. 1677) passed away at a young age, their promise unfulfilled.

The reach was expanded by grandchildren. Augustine Washington, George’s father, came out through Mildred. Fielding Lewis and Robert Lewis were descended from Elizabeth. Augustine Washington Jr. and Mildred Washington contributed to the tapestry. Fielding Lewis Jr., John Augustine Washington, and George Washington, the first president, were all brilliant great-grandchildren. Deeper roots were suggested by even great-great-grandparents like William Warner and Ann Peck, or connections to Sotherton and Thompson.

I see this family as a river that flows into the halls of power from Virginia in the 17th century. Part of the story is revealed by the numbers: Warner Jr. fathered six daughters, but only three of them lived to adulthood, dividing estates totaling more than 33,000 acres.

Career Ascent: Planter, Politician, Militiaman

Diving into Warner Jr.’s professional life feels like uncovering a hidden map of colonial power. He inherited Warner Hall in Gloucester County in 1674, a sprawling tobacco plantation that symbolized wealth, much like a crown atop a king’s head. As a planter, he managed vast lands, including Chesake, relying on indentured servants and enslaved labor to harvest fortunes from the soil.

His political rise was swift. Entering the House of Burgesses in 1666 for Gloucester County, he navigated the turbulent waters of governance. By 1675, appointed militia colonel, he commanded forces amid rising unrest. The pivotal year: 1676, during Bacon’s Rebellion. As Speaker of the House, he stood loyal to Governor Berkeley, even as rebels scorched Warner Hall. Short and sharp: Loyalty paid off. In 1677, he joined the Governor’s Council, retaining his seat through 1679 purges that felled others like Philip Ludwell.

Achievements stacked up. He sued William Byrd for 1,000 pounds in post-rebellion grievances, showcasing tenacity. Financially, his estates burgeoned, tobacco exports fueling a net worth tied to land grants and trade. Militarily, as colonel, he fortified Gloucester against threats. Politically, his council role influenced Virginia’s direction until his death on June 19, 1681, at age 39. Buried at Warner Hall Graveyard, his legacy endured.

To organize his milestones, here’s a table of key career highlights:

| Year | Achievement | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1666 | Entered House of Burgesses | Represented Gloucester County; began political career. |

| 1674 | Inherited Warner Hall | Gained over 33,000 acres; expanded tobacco operations. |

| 1675 | Appointed Militia Colonel | Commanded Gloucester forces amid tensions. |

| 1676 | Elected Speaker | During Bacon’s Rebellion; house damaged by rebels. |

| 1677 | Joined Governor’s Council | Retained seat despite purges; sued William Byrd. |

| 1681 | Death | Ended council service; buried at Warner Hall. |

Enduring Influence and Descendants

Reflecting on Warner Jr.’s impact, I see him as a cornerstone in Virginia’s foundation. His brief 39 years seeded a dynasty. Descendants like George Washington carried his blood into revolution. Robert E. Lee, through sister Sarah, echoed in Civil War echoes. Even British royalty, Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III, trace back as their last common ancestor.

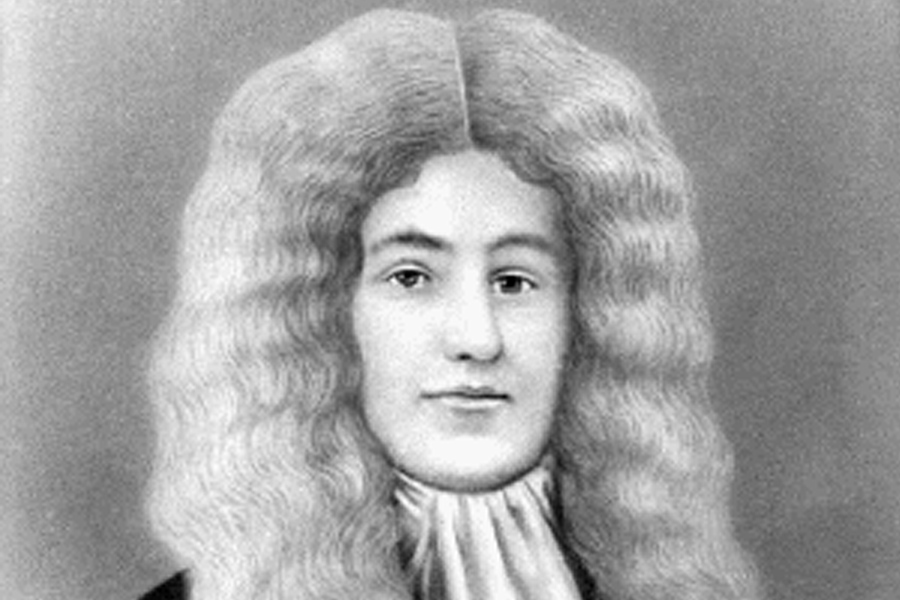

Lesser-known facets intrigue me. Warner Hall, now a bed-and-breakfast, preserves his memory. His education in London equipped him for leadership, blending English poise with colonial grit. Family portraits, possibly of him or his father, evoke mystery. As a headright ancestor, he enabled land grants, fueling expansion.

The rebellion role stands out: A Berkeley loyalist, he avoided personal gains from trials, unlike peers. Tensions with Byrd highlight the era’s frictions. His wealth, over 33,000 acres, underscored the planter elite’s dominance.

FAQ

Who were Augustine Warner Jr.’s parents and what was their background?

His father, Augustine Warner Sr. (1610-1674), immigrated from England around 1628, becoming a planter and councilor. His mother, Mary Towneley (1614-1662), came from Lancashire gentry, bringing noble ties.

How many children did Augustine Warner Jr. have, and who survived?

He had six children: Mary (circa 1664-1700), Augustine III (1666-1687), Mildred (1670-1701), Elizabeth (1672-1720), George (circa 1677), and Robert. Only daughters Mary, Mildred, and Elizabeth survived to adulthood.

What was Warner Jr.’s role in Bacon’s Rebellion?

As Speaker in 1676, he remained loyal to Governor Berkeley. Rebels damaged Warner Hall, but he retained influence, joining the Council in 1677.

How is Augustine Warner Jr. connected to George Washington?

Through daughter Mildred Warner, who married Lawrence Washington, becoming grandmother to Augustine Washington, George’s father. Thus, Warner Jr. is George’s great-grandfather.

What estates did Warner Jr. own?

He inherited Warner Hall in 1674 and owned Chesake, totaling over 33,000 acres focused on tobacco.

Did Warner Jr. have any notable legal actions?

Yes, he sued William Byrd for 1,000 pounds post-rebellion, reflecting grievances without benefiting from confiscations.

What education did Warner Jr. receive?

Enrolled at Merchant Tailors’ School in London in 1658, as the eldest son of a gentleman, gaining metropolitan exposure before returning to Virginia.

How did Warner Jr.’s family link to British royalty?

Daughter Mary’s line led to Queen Elizabeth II; he is the last common ancestor with King Charles III.

What was Mildred Reade’s fate after Warner Jr.’s death?

She remarried Lawrence Washington, then Henry Gale, expanding family connections.

Why is Warner Hall significant today?

Preserved as a bed-and-breakfast, it honors his legacy, with the graveyard holding his remains since 1681.